- January 17, 2019

- Posted by: Rahul Thachilath

- Category: Technology

Package your code and run it everywhere

What are Containers?

Containers provide a standard way to package your application’s code, configurations, and dependencies into a single object. Containers share an operating system installed on the server and run as resource-isolated processes, ensuring quick, reliable, and consistent deployments, regardless of environment.

Different Containers

Docker is the leader among containers. However, there are other containers in place like rkt, Solaris containers, Microsoft containers, etc

Container governance

Open Container Initiative defines the specs regarding the development of containers.

Established in June 2015 by Docker and other leaders in the container industry, the OCI currently contains two specifications: the Runtime Specification (runtime-spec) and the Image Specification (image-spec). The Runtime Specification outlines how to run a “filesystem bundle” that is unpacked on disk. At a high-level, an OCI implementation would download an OCI Image then unpack that image into an OCI Runtime filesystem bundle. At this point, the OCI Runtime Bundle would be run by an OCI Runtime.

Need of Container

Containers allow a developer to package up an application with all of the parts it needs, such as libraries and other dependencies, and ship it all out as one package. By doing so, thanks to the container, the developer can rest assured that the application will run on any other machine regardless of any customized settings that machine might have that could differ from the machine used for writing and testing the code.

In a way, a Container is a bit like a virtual machine. But unlike a virtual machine, rather than creating a whole virtual operating system, A Container allows applications to use the same kernel as the system that they’re running on and only requires applications be shipped with things not already running on the host computer. This gives a significant performance boost and reduces the size of the application.

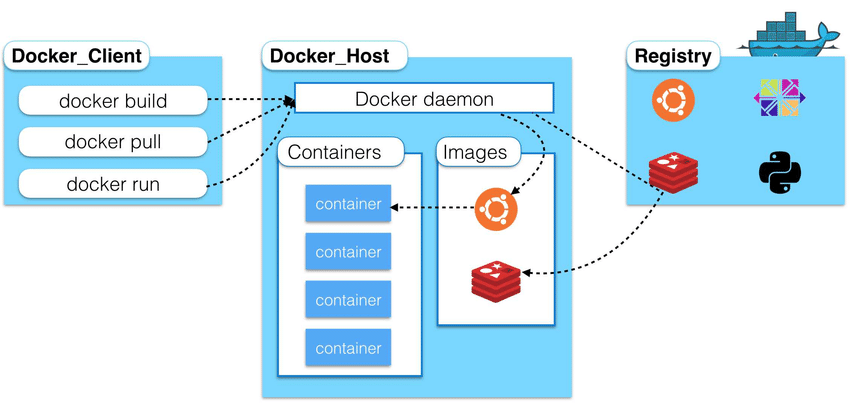

Docker architecture

Docker uses a client-server architecture. The Docker client talks to the Docker daemon, which does the heavy lifting of a building, running, and distributing your Docker containers. The Docker client and daemon can run on the same system, or you can connect a Docker client to a remote Docker daemon. The Docker client and daemon communicate using a REST API, over UNIX sockets or a network interface.

The Docker daemon

The Docker daemon (dockerd) listens for Docker API requests and manages Docker objects such as images, containers, networks, and volumes. A daemon can also communicate with other daemons to manage Docker services.

The Docker client

The Docker client (docker) is the primary way that many Docker users interact with Docker. When you use commands such as docker run, the client sends these commands to dockerd, which carries them out. The docker command uses the Docker API. The Docker client can communicate with more than one daemon.

Docker registries

A Docker registry stores Docker images. Docker Hub is a public registry that anyone can use, and Docker is configured to look for images on Docker Hub by default. You can even run your own private registry. If you use Docker Datacenter (DDC), it includes Docker Trusted Registry (DTR).

When you use the docker pull or docker run commands, the required images are pulled from your configured registry. When you use the docker push command, your image is pushed to your configured registry.

Docker objects

When you use Docker, you are creating and using images, containers, networks, volumes, plugins, and other objects. This section is a brief overview of some of those objects.

IMAGES

An image is a read-only template with instructions for creating a Docker container. Often, an image is based on another image, with some additional customization. For example, you may build an image which is based on the Ubuntu images but installs the Apache web server and your application, as well as the configuration details needed to make your application run.

You might create your own images or you might only use those created by others and published in a registry. To build your own image, you create a Dockerfile with a simple syntax for defining the steps needed to create the image and run it. Each instruction in a Dockerfile creates a layer in the image. When you change the Dockerfile and rebuild the image, only those layers which have changed are rebuilt. This is part of what makes images so lightweight, small, and fast when compared to other virtualization technologies.

CONTAINERS

A container is a runnable instance of an image. You can create, start, stop, move, or delete a container using the Docker API or CLI. You can connect a container to one or more networks, attach storage to it, or even create a new image based on its current state.

By default, a container is relatively well isolated from other containers and its host machine. You can control how isolated a container’s network, storage, or other underlying subsystems are from other containers or from the host machine.

A container is defined by its image as well as any configuration options you provide to it when you create or start it. When a container is removed, any changes to its state that are not stored in persistent storage disappear.